Charlotte Salomon, a young Jewish artist at the Berlin Fine Arts Academy, grew into the rude awakening that there was no place in Germany for artists who painted green skies. Hitler labeled such art works “degenerate,” claimed the artists who made them suffered from an “eye disease,” and vowed to treat them as criminals. Moreover, art made by Jews was by definition considered fraudulent.

In the summer of 1938 Charlotte’s position at the Academy was annulled. A month after Kristallnacht, at the age of twenty-one, she was sent to live with her grandparents in the South of France. Her father Albert Salomon, a distinguished doctor and researcher in mammography, and her stepmother Paula Salomon-Lindberg, a charismatic opera singer, fled to Holland to procure papers. The plan was to meet up with Charlotte in Marseille and sail to America.

Initially Charlotte lived with her grandparents at Villefranche in a cottage on the grounds of L’Ermitage, a chateau owned by the American heiress Ottilie Moore, who recognized Charlotte’s talent, encouraged her work, and became her patron. Moore had been benefactress to Charlotte’s grandparents for a number of years, but conflict erupted between the disgruntled and entitled elderly couple and Moore, when the latter turned her attention away from them and became consumed with providing sanctuary for orphaned children and Jewish refugees. Likely her grandparents would have been asked to leave had Charlotte not first managed to move them out of the cottage at L’Ermitage, away from Villefranche, and into an apartment in Nice.

Within months of the move, shortly before France fell to Germany, Charlotte found her grandmother hanging by the light fixture in the bathroom and managed to save her. It was then her grandfather revealed the family secret: nine people on her mother’s side—including all the women, among them Charlotte’s own mother—had killed themselves.

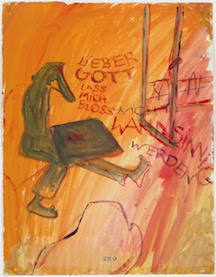

Charlotte sat up all night, keeping watch over herself. In her painting of that vigil, her bedroom airspace is a dense inferno in yellows and oranges. A small easel balances on her lap. The umber lines render it a continuation of her body, as much an appendage as an arm. Scrawled in red across the whole conflagration are these words: Dear God, don’t let me go mad.

Shortly after Charlotte learned of the suicides, her grandmother leaped out the window, plunging to her death. Charlotte became the last living member in her matrilineal line, hounded by her grandfather, who insisted that suicide was her destiny, too.

Opinions differ, but it seems that during the roundup of foreign nationals in the summer of 1940, the Vichy government sent Charlotte and her grandfather, with thousands of others packed into a train, across France to Gurs, a squalid internment camp in the Pyrenées. A few weeks later they were released. Her freedom was conditional: she must be caretaker to her aged grandfather. The penalty for noncompliance would be re-internment. Without food, money, or extra clothing, they had to make the return journey home on foot, hundreds of miles, from western France to Nice. At night her grandfather badgered her to sleep with him. By day he urged her to kill herself and “get it over with already.”

A year passed. Rotterdam stopped issuing visas. Charlotte had no word from her parents. Unable to put up with her grandfather any longer, Charlotte abandoned him. She moved into a pension in tiny St. Jean Cap de Ferrat, where she lived alone without identity papers, risking deportation. In an artistic fury lasting over a year, she created 1300 gouache—dense watercolor—paintings. She remained there, struggling to produce a monument to her life in a race against time before capture by the Nazis.

Charlotte suffered a severe depression in the winter of ’41-42, convinced her work would never be seen. But a breakthrough led the artist to edit and order her paintings, adding narrative, dialogue, and musical prompts. The process transformed a sequence of frames into a story: a coming-of-age in Hitler’s Berlin and a coming-to-terms with her family’s tragic legacy. It became a wry, ironic operetta, entitled Life? Or Theater?.

When she was forced to return to her grandfather, she battled the threat of psychological disintegration and the terror of the encroaching Third Reich in the form of his menacing personage. Driven to a desperate choice, she cooked a deadly dose of veronal into his evening meal.

Meanwhile, Ottilie Moore had returned to America, leaving an Austrian-Jewish refugee as the sole occupant of L’Ermitage. Charlotte found a temporary safe haven there with him, and they became lovers. By creating an identity in art, the sensitive, naïve artist grew into a mature woman, ready for life, as she never had been. Before long Charlotte was pregnant.

The couple’s subsequent marriage left an address record at the Town Hall—a fatal error. The Nazis stormed their hideout and shipped Charlotte and her husband to the transport camp at Drancy, outside Paris. But not before she was able to deliver her masterpiece into safekeeping. At the moment she released the two humble bundles, wrapped in brown parcel paper and tied with string, into the hands of a local doctor, she spoke these words: “This is my whole life.”

Among the one thousand souls shut inside the freight cars of Transport 60, Charlotte Salomon and her husband left Drancy, bound for the East. On October 10, 1943, at age twenty-six and five months pregnant, Charlotte Salomon arrived in Auschwitz and was immediately gassed.

Having survived in hiding, her father and stepmother went in search of Charlotte after the war and discovered her work. Art critic Griselda Pollock calls Life? Or Theater? “one of the twentieth century’s most challenging art works.” Its home is now the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam. The complete work (paintings, music, and narrative) can be experienced online.

To know how Charlotte Salomon’s art helps one contemporary woman artist navigate trauma, read my short story, “The Bridge,” which first appeared in the Alabama Literary Review.

To read more about Charlotte Salomon, you might be interested in these works:

-

To Paint Her Life: Charlotte Salomon in the Nazi Era by Mary Lowenthal Felstiner. A biography.

-

Nothing Happened: Charlotte Salomon and an Archive of Suicide by Darcy C. Buerkle. Salomon’s Life? Or Theater? as evidence of the erasure of German Jewish female suicide from the historical record.

-

Charlotte Salomon and the Theatre of Memory by Griselda Pollock. An art-historical analysis of Life? Or Theater?

-

Reading Charlotte Salomon edited by Michael P. Steinberg and Monica Bohm-Duchen. An anthology of essays of Salomon’s work by critics and historians from a range of disciplines.

[Photo courtesy of

Collection Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam.

© Charlotte Salomon Foundation

Charlotte Salomon ®

https://jck.nl/en/page/charlotte-salomon-work]

You must be logged in to post a comment.